Beijing's Maduro Problem

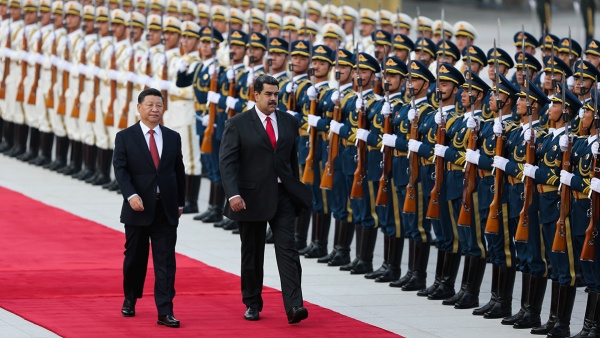

By Chasen Richards, ’19Soon after Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaido was declared interim president by the country’s national assembly, the US and key allies in Europe and Latin America threw in their support, offering aid and materiel to shore up Guaido’s claims to legitimacy. At the same time, a countervailing group solidified behind the ailing Maduro regime, led by Russia, South Africa and, unsurprisingly, China. At first glance, this policy stance seems in line with Beijing’s emphasis on self-determination and non-interventionism, but China has significant interests in Venezuela beyond the value of sticking to a foreign policy talking point. From the early days of the Chavez regime, Beijing has sunk significant financial and political capital into Venezuela, and the collapse of its successor, the China-friendly Maduro regime, would not only lead to immense economic cost, but may cast a pall on a major aspect of Beijing’s foreign policy strategy in the developing world.Beijing’s Pivot to Latin AmericaDevelopmental aid has been a key feature in the Chinese foreign policy process, and Beijing has pumped billions of dollars into underdeveloped economies around the world, especially those with strategic positioning or natural resources. Latin American countries often possess both, and Venezuela’s gargantuan oil deposits have made it a country of interest for China, which consumes 13% of the world’s annual oil production. This pivot to Latin America also served political purposes. As China needed to secure both external resources to bolster economic development and new markets for surplus domestic product, it also needed to find sympathetic partners lacking overly strong ties to the Western sphere of influence. Soon after Bolivarian revolutionist Hugo Chavez came to power in 1999, his hostile stance to the United States demonstrated that he could be a valuable regional ally to Beijing.The patronage that followed took the form of billions of dollars of aid with repayment fixed to future oil contracts. When oil prices were high, spiking first to over $60/barrel in 2005 and then to almost $100/barrel in 2008, the Chavez regime was easily able to service its debt obligations and spend heavily on domestic development and, concerningly, political graft. Nine years into the Chavez regime, Venezuela had taken in almost $300 Billion USD in oil revenue and public debt skyrocketed to $77 Billion USD, over 300%. This massive influx in income has not been reflected in the material conditions of the average Venezuelan. While literacy rates and average income did increase under the Chavez regime, the capital outflows, which are difficult to calculate given the lack of accounting transparency, dwarf any apparent domestic investment. Political corruption has infested every facet of public affairs in Bolivarian Venezuela, allowing anyone from the government elite to average workers in the state-owned oil giant Pedevesa to engage in corrupt, extractive practices.Falling Oil Prices and Failing ProspectsThe result of this trend has been an intensification of the Dutch Disease, which describes the overdependence of many developing countries on one abundant resource to the detriment of other domestic industries. The Chavez regime refrained from diversifying the Venezuelan economy away from petrochemicals, so when the price began to fall, Chavez’s successor Nicolas Maduro was saddled with mountains of debt and an oil-dependent country.The ensuing economic contraction should have put off further Chinese investment, but Beijing seemed to double down on its commitment to the Venezuelan state, supplying an additional $4 Billion dollars in aid to keep the regime afloat as oil prices continue to crater and the lack of investment in Pedevesa’s infrastructure decreases crude oil output by more than a third. To make matters worse, recent political turmoil and popular unrest against Maduro, in addition to the broad international support for Guiado, has presented significant financial and political risk to Beijing.In terms of financial cost, the additional aid that the Chinese government provided Maduro is likely of dubious legality. If the regime falls, it is highly likely that Juan Guiado’s new government will be able to discharge much of that debt, especially with support from American and European allies. Beijing is unwilling to take a $20 Billion loss, especially after claims that the loans offered by its foreign policy centerpiece, The Belt and Road Initiative, are extractive, unfavorable and, most disturbingly, unprofitable. Seeing Chinese opposition as a major roadblock to his accession, Guiado has entered into talks with Chinese foreign authorities, and insider reports suggest that the two parties have discussed a grace period should Guiado take power and more transparent terms for a restructured debt obligation.Belt and RoadblockFor the PRC’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Chinese loans entering the narrative of Venezuela’s collapse adds unneeded complications to an already roundly criticized foreign policy initiative. The Washington-based Center for Global Development identified 23 of the 68 countries involved in the project as receiving high-risk loans. Given the recent seizure of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port by a Chinese state-owned port operator following the country’s default on developmental loans, the global community has viewed China’s dollar diplomacy with increasing scrutiny. As the BRI comes under fire, the very public failure of a beneficiary state like Venezuela may not only validate criticism of the project but could redirect the active policy interests of the United States and its allies towards the larger issues of China’s foreign financing. The preservation of the Maduro regime, or at least a transition that minimizes the potentially crippling effects of a debt crisis, is necessary to avoid increased international scrutiny towards the program.The Sino-Venezuelan relationship yielded gains for both China’s economic and foreign policy objectives, much as the BRI does. But as the Maduro regime flounders, the fallout may split the two and could compel China to choose between maintaining a key ally in Latin America and its current economic and developmental interests.

By Chasen Richards, ’19Soon after Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaido was declared interim president by the country’s national assembly, the US and key allies in Europe and Latin America threw in their support, offering aid and materiel to shore up Guaido’s claims to legitimacy. At the same time, a countervailing group solidified behind the ailing Maduro regime, led by Russia, South Africa and, unsurprisingly, China. At first glance, this policy stance seems in line with Beijing’s emphasis on self-determination and non-interventionism, but China has significant interests in Venezuela beyond the value of sticking to a foreign policy talking point. From the early days of the Chavez regime, Beijing has sunk significant financial and political capital into Venezuela, and the collapse of its successor, the China-friendly Maduro regime, would not only lead to immense economic cost, but may cast a pall on a major aspect of Beijing’s foreign policy strategy in the developing world.Beijing’s Pivot to Latin AmericaDevelopmental aid has been a key feature in the Chinese foreign policy process, and Beijing has pumped billions of dollars into underdeveloped economies around the world, especially those with strategic positioning or natural resources. Latin American countries often possess both, and Venezuela’s gargantuan oil deposits have made it a country of interest for China, which consumes 13% of the world’s annual oil production. This pivot to Latin America also served political purposes. As China needed to secure both external resources to bolster economic development and new markets for surplus domestic product, it also needed to find sympathetic partners lacking overly strong ties to the Western sphere of influence. Soon after Bolivarian revolutionist Hugo Chavez came to power in 1999, his hostile stance to the United States demonstrated that he could be a valuable regional ally to Beijing.The patronage that followed took the form of billions of dollars of aid with repayment fixed to future oil contracts. When oil prices were high, spiking first to over $60/barrel in 2005 and then to almost $100/barrel in 2008, the Chavez regime was easily able to service its debt obligations and spend heavily on domestic development and, concerningly, political graft. Nine years into the Chavez regime, Venezuela had taken in almost $300 Billion USD in oil revenue and public debt skyrocketed to $77 Billion USD, over 300%. This massive influx in income has not been reflected in the material conditions of the average Venezuelan. While literacy rates and average income did increase under the Chavez regime, the capital outflows, which are difficult to calculate given the lack of accounting transparency, dwarf any apparent domestic investment. Political corruption has infested every facet of public affairs in Bolivarian Venezuela, allowing anyone from the government elite to average workers in the state-owned oil giant Pedevesa to engage in corrupt, extractive practices.Falling Oil Prices and Failing ProspectsThe result of this trend has been an intensification of the Dutch Disease, which describes the overdependence of many developing countries on one abundant resource to the detriment of other domestic industries. The Chavez regime refrained from diversifying the Venezuelan economy away from petrochemicals, so when the price began to fall, Chavez’s successor Nicolas Maduro was saddled with mountains of debt and an oil-dependent country.The ensuing economic contraction should have put off further Chinese investment, but Beijing seemed to double down on its commitment to the Venezuelan state, supplying an additional $4 Billion dollars in aid to keep the regime afloat as oil prices continue to crater and the lack of investment in Pedevesa’s infrastructure decreases crude oil output by more than a third. To make matters worse, recent political turmoil and popular unrest against Maduro, in addition to the broad international support for Guiado, has presented significant financial and political risk to Beijing.In terms of financial cost, the additional aid that the Chinese government provided Maduro is likely of dubious legality. If the regime falls, it is highly likely that Juan Guiado’s new government will be able to discharge much of that debt, especially with support from American and European allies. Beijing is unwilling to take a $20 Billion loss, especially after claims that the loans offered by its foreign policy centerpiece, The Belt and Road Initiative, are extractive, unfavorable and, most disturbingly, unprofitable. Seeing Chinese opposition as a major roadblock to his accession, Guiado has entered into talks with Chinese foreign authorities, and insider reports suggest that the two parties have discussed a grace period should Guiado take power and more transparent terms for a restructured debt obligation.Belt and RoadblockFor the PRC’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Chinese loans entering the narrative of Venezuela’s collapse adds unneeded complications to an already roundly criticized foreign policy initiative. The Washington-based Center for Global Development identified 23 of the 68 countries involved in the project as receiving high-risk loans. Given the recent seizure of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port by a Chinese state-owned port operator following the country’s default on developmental loans, the global community has viewed China’s dollar diplomacy with increasing scrutiny. As the BRI comes under fire, the very public failure of a beneficiary state like Venezuela may not only validate criticism of the project but could redirect the active policy interests of the United States and its allies towards the larger issues of China’s foreign financing. The preservation of the Maduro regime, or at least a transition that minimizes the potentially crippling effects of a debt crisis, is necessary to avoid increased international scrutiny towards the program.The Sino-Venezuelan relationship yielded gains for both China’s economic and foreign policy objectives, much as the BRI does. But as the Maduro regime flounders, the fallout may split the two and could compel China to choose between maintaining a key ally in Latin America and its current economic and developmental interests.