America's Involvement in Afghanistan Drawing to a Close

By Alexander Clark, '19Left: US troops in Afghanistan (Credit: Council on Foreign Relations)America’s longest war seems to be entering its final stage. On January 28th, US Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad reported on a successful deal framework which could allow for US withdrawal from Afghanistan, forged after six days of US-Taliban talks in Doha, Qatar. The Framework stipulates that the Taliban, which ruled Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 and is currently fighting an insurgency against the US-backed Afghan government, must not give safe haven to terror groups such as Al Qaeda or the Islamic State in order for US troops to leave. While the Taliban has agreed to this basic provision, it is far more averse to engaging in direct talks based on a ceasefire with the Afghan government. The US also labels these developments as necessary for a total US withdrawal from Afghanistan. Upon concluding the Doha talks, the Taliban representatives have requested further time to deliberate on US preconditions for a ceasefire and talks with the Afghan government according to an anonymous US official familiar with the matter, reports the New York Times. President Donald Trump spoke favorably of these developments during his annual state of the union address. He remarked during this speech to a joint session of congress: “My administration is holding constructive talks with a number of Afghan groups, including the Taliban. As we make progress in these negotiations, we will be able to reduce our troop presence and focus on counter-terrorism."Famed diplomat Ryan Crocker has argued that the Taliban will eventually retake Afghanistan, claiming that the current negotiations are just a way for the US to save face in the hopes of maintaining a high international reputation as it exits a deeply unpopular, nearly 20 year-long war, which began in 2001 after Al Qaeda, based in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, carried out the September 11th terror attacks.“I think the entire dynamic suggests that we’re done in Afghanistan, we’re going to get out. Let’s negotiate something that at least looks like a political agreement rather than an all-out surrender...Rather like Syria, I think the president has signaled the end state, and we’re just negotiating the terms now.,” Crocker told Foreign Policy Magazine on the current US-Taliban negotiations.He did not seem particular hopeful going forward that the US would press the Taliban on negotiating directly with the American-backed Afghan central government in Kabul, given President Trump’s eagerness to end the war.To Foreign Policy and the New York Times, Mr. Crocker compared the talks in Doha to the Paris Peace Accords of 1973 which set the terms for the end of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War.“By going to the table, we basically were telling the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong, ‘We surrender, we’re here just to work out the terms...I just cannot see this getting to any better place. We don’t have a whole lot of leverage here. I can’t see this as anything more than putting lipstick on what will be a U.S. withdrawal,” Mr. Crocker told the New York Times Above: Taliban fighters in the Ghanikhel district of Nangarhar province, Afghanistan (Credit: Al Jazeera)

By Alexander Clark, '19Left: US troops in Afghanistan (Credit: Council on Foreign Relations)America’s longest war seems to be entering its final stage. On January 28th, US Envoy Zalmay Khalilzad reported on a successful deal framework which could allow for US withdrawal from Afghanistan, forged after six days of US-Taliban talks in Doha, Qatar. The Framework stipulates that the Taliban, which ruled Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 and is currently fighting an insurgency against the US-backed Afghan government, must not give safe haven to terror groups such as Al Qaeda or the Islamic State in order for US troops to leave. While the Taliban has agreed to this basic provision, it is far more averse to engaging in direct talks based on a ceasefire with the Afghan government. The US also labels these developments as necessary for a total US withdrawal from Afghanistan. Upon concluding the Doha talks, the Taliban representatives have requested further time to deliberate on US preconditions for a ceasefire and talks with the Afghan government according to an anonymous US official familiar with the matter, reports the New York Times. President Donald Trump spoke favorably of these developments during his annual state of the union address. He remarked during this speech to a joint session of congress: “My administration is holding constructive talks with a number of Afghan groups, including the Taliban. As we make progress in these negotiations, we will be able to reduce our troop presence and focus on counter-terrorism."Famed diplomat Ryan Crocker has argued that the Taliban will eventually retake Afghanistan, claiming that the current negotiations are just a way for the US to save face in the hopes of maintaining a high international reputation as it exits a deeply unpopular, nearly 20 year-long war, which began in 2001 after Al Qaeda, based in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan, carried out the September 11th terror attacks.“I think the entire dynamic suggests that we’re done in Afghanistan, we’re going to get out. Let’s negotiate something that at least looks like a political agreement rather than an all-out surrender...Rather like Syria, I think the president has signaled the end state, and we’re just negotiating the terms now.,” Crocker told Foreign Policy Magazine on the current US-Taliban negotiations.He did not seem particular hopeful going forward that the US would press the Taliban on negotiating directly with the American-backed Afghan central government in Kabul, given President Trump’s eagerness to end the war.To Foreign Policy and the New York Times, Mr. Crocker compared the talks in Doha to the Paris Peace Accords of 1973 which set the terms for the end of America’s involvement in the Vietnam War.“By going to the table, we basically were telling the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong, ‘We surrender, we’re here just to work out the terms...I just cannot see this getting to any better place. We don’t have a whole lot of leverage here. I can’t see this as anything more than putting lipstick on what will be a U.S. withdrawal,” Mr. Crocker told the New York Times Above: Taliban fighters in the Ghanikhel district of Nangarhar province, Afghanistan (Credit: Al Jazeera) Left: Taliban fighters in the Ghanikhel district of Nangarhar province, Afghanistan (Credit: Al Jazeera)Other voices, however, say it is finally time for the US to pack up and leave, saying it cannot realistically accomplish any further substantive goals in Afghanistan, where the Taliban insurgency controls approximately 14% of the country’s districts. Professor Anatol Lieven, writing for Foreign Policy, argues that the Taliban is committed to never hosting a group like Al-Qaeda again because it resulted in their toppling after the September 11th attacks. He further argues for Afghanistan’s neighbors and regional powers of India, Pakistan, Iran, China and Russia to play a role in stabilizing the country following a US exit. Even though these countries, excluding India, have cold relations with the US, they have a stake in ensuring a viable long-term stability. For example, Lieven points out that Iran and Russia have been devastated by the Afghan heroin trade and so they have an interest in ensuring this disastrous drug does not figure in Afghanistan’s future. He also points out that the Taliban will likely clamp down on it, given their success in doing so from 1999-2001. Still, Lieven concedes that the future of Afghanistan is far from certain, and that some sort of power-sharing agreement between the Taliban and the current Afghan government, which he envisions as ideal, would be vociferously opposed by America’s allies in that government. He also more or less agrees with Ryan Crocker’s assessment on the current negotiations serving as a cynical way for the US to save face, and maintain “prestige” which in Lieven’s words masks behind the foreign affairs buzzword, “credibility.”

Left: Taliban fighters in the Ghanikhel district of Nangarhar province, Afghanistan (Credit: Al Jazeera)Other voices, however, say it is finally time for the US to pack up and leave, saying it cannot realistically accomplish any further substantive goals in Afghanistan, where the Taliban insurgency controls approximately 14% of the country’s districts. Professor Anatol Lieven, writing for Foreign Policy, argues that the Taliban is committed to never hosting a group like Al-Qaeda again because it resulted in their toppling after the September 11th attacks. He further argues for Afghanistan’s neighbors and regional powers of India, Pakistan, Iran, China and Russia to play a role in stabilizing the country following a US exit. Even though these countries, excluding India, have cold relations with the US, they have a stake in ensuring a viable long-term stability. For example, Lieven points out that Iran and Russia have been devastated by the Afghan heroin trade and so they have an interest in ensuring this disastrous drug does not figure in Afghanistan’s future. He also points out that the Taliban will likely clamp down on it, given their success in doing so from 1999-2001. Still, Lieven concedes that the future of Afghanistan is far from certain, and that some sort of power-sharing agreement between the Taliban and the current Afghan government, which he envisions as ideal, would be vociferously opposed by America’s allies in that government. He also more or less agrees with Ryan Crocker’s assessment on the current negotiations serving as a cynical way for the US to save face, and maintain “prestige” which in Lieven’s words masks behind the foreign affairs buzzword, “credibility.”

Left: US soldiers and Afghan border police along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border (Credit: Department of Defense)Hussein Haqqani, the former Pakistani ambassador to the United States, lambasted the Trump administration’s plans for Afghanistan as destined for failure given its lack of engaging Pakistan over its continued sheltering and aiding of the Taliban. He views Trump’s laser-focus on withdrawal, instead of creating stability, as an enduring shortcoming in American policy toward Afghanistan which has benefited Pakistan’s long-term project in creating a staunch Islamic anti-Indian ally out of its northern neighbor. In this context, the Afghan people will be the greatest losers from any US-Taliban deal for an American withdrawal, which Haqqani believes will lead to escalated civil war in the country, much like the Soviet withdrawal in 1989.While Haqqani brings up legitimate points, the question remains as to how America can effectively stabilize Afghanistan in the long term. American counterinsurgency campaigns according to Stephen B Young have continuously stressed the number of insurgents killed as victory. This mistake has been repeated from Vietnam to Afghanistan, while the US has ignored creating a long-lasting political settlement.Indeed, Mr. Young implies that American frustration with “nation building”, which Mr. Trump capitalized on during his 2016 ‘America First’ campaign, is misplaced since it has not been stressed as a priority of US military policy in war torn regions.

Left: US soldiers and Afghan border police along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border (Credit: Department of Defense)Hussein Haqqani, the former Pakistani ambassador to the United States, lambasted the Trump administration’s plans for Afghanistan as destined for failure given its lack of engaging Pakistan over its continued sheltering and aiding of the Taliban. He views Trump’s laser-focus on withdrawal, instead of creating stability, as an enduring shortcoming in American policy toward Afghanistan which has benefited Pakistan’s long-term project in creating a staunch Islamic anti-Indian ally out of its northern neighbor. In this context, the Afghan people will be the greatest losers from any US-Taliban deal for an American withdrawal, which Haqqani believes will lead to escalated civil war in the country, much like the Soviet withdrawal in 1989.While Haqqani brings up legitimate points, the question remains as to how America can effectively stabilize Afghanistan in the long term. American counterinsurgency campaigns according to Stephen B Young have continuously stressed the number of insurgents killed as victory. This mistake has been repeated from Vietnam to Afghanistan, while the US has ignored creating a long-lasting political settlement.Indeed, Mr. Young implies that American frustration with “nation building”, which Mr. Trump capitalized on during his 2016 ‘America First’ campaign, is misplaced since it has not been stressed as a priority of US military policy in war torn regions. Left: Acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan in Afghanistan (Credit: Robert Burns/Associated Press/Wall Street Journal)Quite simply, the American people as a whole have moved on from Afghanistan, as the phrase, “endless war” has entered the contemporary political lexicon. Even so, the inconsistency of the Trump administration, along with its difficulty in following through on pronouncements, must be considered. Despite Trump’s bold proclamations of ending “endless war,” acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan announced that no troop withdrawal from the 14,000-strong US force in Afghanistan was forthcoming during a surprise visit to the country on February 11th, even as Taliban official Abdul Salam Hanafi sparked denials among US military officials after saying that the Americans would withdraw half of their forces by April.This trend of statements from the Trump administration contradicting the facts on the ground extends well beyond Afghanistan. Donald Trump recently announced that US troops would be coming home from Syria, but the withdrawal has yet to be ordered due to key diplomatic hurdles. Actors such as the Kurds, Turkey and Bashar Al Assad’s Syria all have their own agendas in filling the power vacuum in North Eastern Syria which US forces would abandon upon withdrawal, set for a tentative April deadline per the Wall Street Journal. While President Trump promised to withdraw around 2,000 troops from Syria in December, 3,000 US troops remain in the country as of early February, albeit to protect the US withdrawal the New York Times reports. In short, a highly murky picture is taking shape regarding Syria’s future, one far more complex than Mr. Trump’s promised simple exit strategy by tweet. Such contradictions in Afghanistan will undoubtedly dog Trump as well as well. Indeed, he inherited this conflict even though his predecessor, Barack Obama, expressed hopes to end the conflict before he left office.In the context of these negotiations with the Taliban, the US under General Austin S. Miller is also leading a strategy of heightened US military action to force a more favorable peace settlement. The New York Times reports this strategy as akin to the US military’s bombing campaign of Vietnam, Operation Linebacker II, launched in the closing phase of the war to gain a favorable settlement with the North Vietnamese. Miller, in coordination with America’s Afghan allies, is leading a war of attrition against the Taliban before conflict intensifies after the Afghan snow melts in a time known as “the fighting season.” Since September, the US has conducted 2,100 air and artillery strikes on Afghanistan, and joint US-Afghan raids have doubled since then relative to the same 5 month period last year according to the same New York Times report. The renewed offensive has taken its toll on US forces with US commando casualties in January, 2 dead and 2 dozen wounded, exceeding those of the entirety of 2018.Still, those numbers pale in comparison to what the Afghan military has experienced, with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani admitting that 45,000 Afghan security forces have been killed in battle since 2014, a staggering number well beyond what the government was initially willing to disclose to the public.The high losses endured by the Afghan security forces are “unsustainable” according to US military official Kenneth McKenzie per Reuters. He said this in the context of perceived Afghan military losses being at the lower number of 28,000 since 2015.He continued, “If we left precipitously right now, I do not believe they would be able to successfully defend their country.”McKenzie estimated that Taliban forces number at around 60,000. These forces further aided by neighboring Pakistan, a precipitous relationship from the US perspective detailed previously by the Cornell Current and cited by Husain Haqqani as the reason for the Taliban’s enduring strength and successes on the battlefield.

Left: Acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan in Afghanistan (Credit: Robert Burns/Associated Press/Wall Street Journal)Quite simply, the American people as a whole have moved on from Afghanistan, as the phrase, “endless war” has entered the contemporary political lexicon. Even so, the inconsistency of the Trump administration, along with its difficulty in following through on pronouncements, must be considered. Despite Trump’s bold proclamations of ending “endless war,” acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan announced that no troop withdrawal from the 14,000-strong US force in Afghanistan was forthcoming during a surprise visit to the country on February 11th, even as Taliban official Abdul Salam Hanafi sparked denials among US military officials after saying that the Americans would withdraw half of their forces by April.This trend of statements from the Trump administration contradicting the facts on the ground extends well beyond Afghanistan. Donald Trump recently announced that US troops would be coming home from Syria, but the withdrawal has yet to be ordered due to key diplomatic hurdles. Actors such as the Kurds, Turkey and Bashar Al Assad’s Syria all have their own agendas in filling the power vacuum in North Eastern Syria which US forces would abandon upon withdrawal, set for a tentative April deadline per the Wall Street Journal. While President Trump promised to withdraw around 2,000 troops from Syria in December, 3,000 US troops remain in the country as of early February, albeit to protect the US withdrawal the New York Times reports. In short, a highly murky picture is taking shape regarding Syria’s future, one far more complex than Mr. Trump’s promised simple exit strategy by tweet. Such contradictions in Afghanistan will undoubtedly dog Trump as well as well. Indeed, he inherited this conflict even though his predecessor, Barack Obama, expressed hopes to end the conflict before he left office.In the context of these negotiations with the Taliban, the US under General Austin S. Miller is also leading a strategy of heightened US military action to force a more favorable peace settlement. The New York Times reports this strategy as akin to the US military’s bombing campaign of Vietnam, Operation Linebacker II, launched in the closing phase of the war to gain a favorable settlement with the North Vietnamese. Miller, in coordination with America’s Afghan allies, is leading a war of attrition against the Taliban before conflict intensifies after the Afghan snow melts in a time known as “the fighting season.” Since September, the US has conducted 2,100 air and artillery strikes on Afghanistan, and joint US-Afghan raids have doubled since then relative to the same 5 month period last year according to the same New York Times report. The renewed offensive has taken its toll on US forces with US commando casualties in January, 2 dead and 2 dozen wounded, exceeding those of the entirety of 2018.Still, those numbers pale in comparison to what the Afghan military has experienced, with Afghan President Ashraf Ghani admitting that 45,000 Afghan security forces have been killed in battle since 2014, a staggering number well beyond what the government was initially willing to disclose to the public.The high losses endured by the Afghan security forces are “unsustainable” according to US military official Kenneth McKenzie per Reuters. He said this in the context of perceived Afghan military losses being at the lower number of 28,000 since 2015.He continued, “If we left precipitously right now, I do not believe they would be able to successfully defend their country.”McKenzie estimated that Taliban forces number at around 60,000. These forces further aided by neighboring Pakistan, a precipitous relationship from the US perspective detailed previously by the Cornell Current and cited by Husain Haqqani as the reason for the Taliban’s enduring strength and successes on the battlefield.  Above: Afghan national army troops on parade in Kabul in November, 2012 (Credit: Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty)One can talk about the highly corrupt central government in Kabul, its struggling military, the loss of around 2,300 US soldiers in Afghanistan, the $1 trillion the US has spent on the conflict since 2001 and the burgeoning Afghan drug trade which America and its allies catastrophically failed in containing. The failure of US foreign policy in Afghanistan greatly exceeds the sum of its many, significant parts, illustrating time and again how even rudimentary insurgencies can drag down highly advanced militaries without clear commitments, motivation or strategy. For this publication, I wrote about the dangers of America repeating the mistakes of other powers who conducted military campaigns in Afghanistan. Upon reflection, it seems that any support for America’s continued involvement in Afghanistan is a moot point, given the growing consensus that this war appears to have been lost.Still as commander in chief, Donald Trump seems incapable of following through on implementing orders for troop withdrawals given the general confusion surrounding Syria. His own legal troubles at home and general unpopularity heading into the 2020 elections could also mean he might not be in office much longer. Following in the footsteps of Bush and Obama, Donald Trump may be the third president to have America’s forever war outlast his administration.Still, whatever the political fate of Donald Trump, his potential 2020 challengers such as Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Kristine Gillibrand and Corey Booker all voted against a senate resolution condemning Trump’s drawdown, signaling that if in office, they would likely continue the process of withdrawal. They would have a broad mandate, considering that in 2013 the war became more unpopular than Vietnam.As America arguably prepares to leave Afghanistan, perhaps a new understanding could be reached in American foreign policy circles on the failures of the post 9/11 era of “forever wars.” America must rethink its foreign policy more broadly as well, given the country’s increasing isolation on the world stage, the collapse of confidence in multilateralism, the alarming rise of China and the dysfunction of our internal politics making our country less of a model abroad. These problems go way beyond Donald Trump, indeed he is largely the symptom of the failures of a bipartisan foreign policy elite, which he lambasted during his 2016 campaign, stretching back to the aftermath of the Cold War.

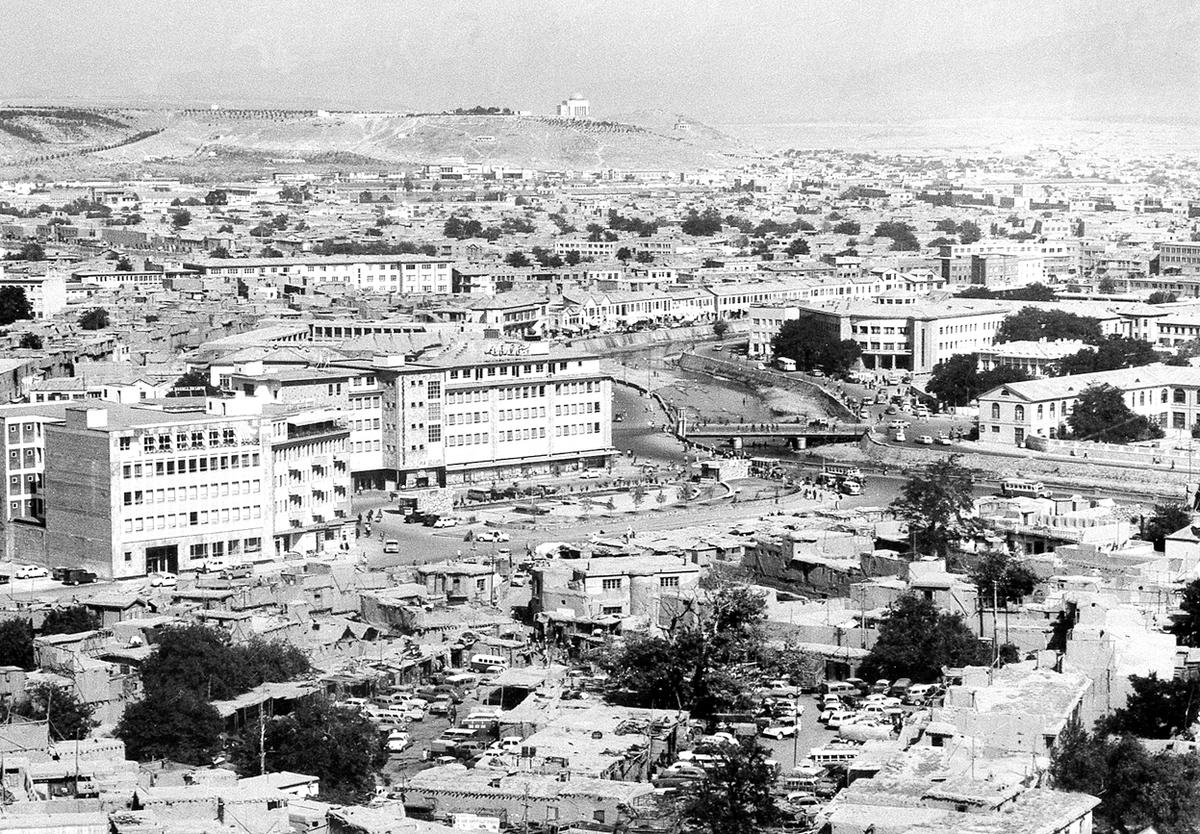

Above: Afghan national army troops on parade in Kabul in November, 2012 (Credit: Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty)One can talk about the highly corrupt central government in Kabul, its struggling military, the loss of around 2,300 US soldiers in Afghanistan, the $1 trillion the US has spent on the conflict since 2001 and the burgeoning Afghan drug trade which America and its allies catastrophically failed in containing. The failure of US foreign policy in Afghanistan greatly exceeds the sum of its many, significant parts, illustrating time and again how even rudimentary insurgencies can drag down highly advanced militaries without clear commitments, motivation or strategy. For this publication, I wrote about the dangers of America repeating the mistakes of other powers who conducted military campaigns in Afghanistan. Upon reflection, it seems that any support for America’s continued involvement in Afghanistan is a moot point, given the growing consensus that this war appears to have been lost.Still as commander in chief, Donald Trump seems incapable of following through on implementing orders for troop withdrawals given the general confusion surrounding Syria. His own legal troubles at home and general unpopularity heading into the 2020 elections could also mean he might not be in office much longer. Following in the footsteps of Bush and Obama, Donald Trump may be the third president to have America’s forever war outlast his administration.Still, whatever the political fate of Donald Trump, his potential 2020 challengers such as Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Kristine Gillibrand and Corey Booker all voted against a senate resolution condemning Trump’s drawdown, signaling that if in office, they would likely continue the process of withdrawal. They would have a broad mandate, considering that in 2013 the war became more unpopular than Vietnam.As America arguably prepares to leave Afghanistan, perhaps a new understanding could be reached in American foreign policy circles on the failures of the post 9/11 era of “forever wars.” America must rethink its foreign policy more broadly as well, given the country’s increasing isolation on the world stage, the collapse of confidence in multilateralism, the alarming rise of China and the dysfunction of our internal politics making our country less of a model abroad. These problems go way beyond Donald Trump, indeed he is largely the symptom of the failures of a bipartisan foreign policy elite, which he lambasted during his 2016 campaign, stretching back to the aftermath of the Cold War.  Above: Kabul, Afghanistan in August, 1969, a panoramic view contrasting old and new buildings during the country’s modernization era (Credit: The Atlantic) With this depressing picture, one can remain hopeful that perhaps Afghanistan is not permanently destined for war and state collapse. Before the Soviet invasion, Afghanistan was a poor country, but nowhere near the depressing, chaotic state it is in today. Indeed, in the 1950s and 60s, it made small, tentative, but nonetheless important steps toward reform and modernization as a conservative Islamic society. While China’s One Belt One Road Initiative has key flaws worthy of harsh criticism, perhaps its mega infrastructure projects spanning Asia could have some promise in putting the war-torn nation on the long path to lasting peace, prosperity and stability. Nikkei’s Asian Review reports former Pakistani Ambassador Qazi Humayun as predicting that the China Pakistan economic corridor will one day extend to Afghanistan.Hopefully, America will learn from the mistakes of this war, and recognize the positive role it can play in foreign affairs beyond the armed conflicts of the post 9/11 era and the Cold War style posturing which the Trump administration defines as “great power competition.” This new recognition could make the world and the US more stable and prosperous in the face of the 21st century’s highly uncertain, yet surmountable challenges.This tragic analysis would be incomplete without the thoughts of average Afghans as well, beyond the military, political class or Taliban. While these opinions are undoubtedly highly varied, with opinions on the Taliban especially contrasting in the cities and countryside, Omid Arman, a 21 year old of Kabul, undoubtedly captured widespread sentiments in his remarks on America’s Afghanistan withdrawal to the Atlantic."Everyone has the desire for peace in this country. We've witnessed a lot of conflicts; it's enough. We don't want to be witnesses for any more tragedy.”

Above: Kabul, Afghanistan in August, 1969, a panoramic view contrasting old and new buildings during the country’s modernization era (Credit: The Atlantic) With this depressing picture, one can remain hopeful that perhaps Afghanistan is not permanently destined for war and state collapse. Before the Soviet invasion, Afghanistan was a poor country, but nowhere near the depressing, chaotic state it is in today. Indeed, in the 1950s and 60s, it made small, tentative, but nonetheless important steps toward reform and modernization as a conservative Islamic society. While China’s One Belt One Road Initiative has key flaws worthy of harsh criticism, perhaps its mega infrastructure projects spanning Asia could have some promise in putting the war-torn nation on the long path to lasting peace, prosperity and stability. Nikkei’s Asian Review reports former Pakistani Ambassador Qazi Humayun as predicting that the China Pakistan economic corridor will one day extend to Afghanistan.Hopefully, America will learn from the mistakes of this war, and recognize the positive role it can play in foreign affairs beyond the armed conflicts of the post 9/11 era and the Cold War style posturing which the Trump administration defines as “great power competition.” This new recognition could make the world and the US more stable and prosperous in the face of the 21st century’s highly uncertain, yet surmountable challenges.This tragic analysis would be incomplete without the thoughts of average Afghans as well, beyond the military, political class or Taliban. While these opinions are undoubtedly highly varied, with opinions on the Taliban especially contrasting in the cities and countryside, Omid Arman, a 21 year old of Kabul, undoubtedly captured widespread sentiments in his remarks on America’s Afghanistan withdrawal to the Atlantic."Everyone has the desire for peace in this country. We've witnessed a lot of conflicts; it's enough. We don't want to be witnesses for any more tragedy.”